If we think of deception as false information disguised as true, it follows that methods of information disguise will often be the first “orange-flags” to suspend our “truth-default” assumptions (Levine, 2020) that people are being cooperative and truthful. Early information anomalies are often the “trigger events” that suspend our naive expectations and arouse deeper curiosity. And once our natural assumptions of truth and cooperation are suspended, deception detection usually results from further analysis and corroboration. To the extent deception is strategically disguised information that exploits our natural perceptual expectations, we must understand our own believability biases and why we assume cooperation and veracity so often and readily.

Information management is a part of all our lives

We all understand and accept our professional, legal and ethical disclosure boundaries in personal and professional contexts; where information is managed for valid reasons. Conversely, we also understand how information can be manipulated for purely transactional or self-serving reasons. But if you think about the last time you were managing problematic information that challenged these constraints, you may recall wanting to avoid or reduce unwanted conversations or, if compelled to have the difficult conversation, avoid problematic topics. Perhaps you were directly asked to address problematic issues, and you manipulated, filtered or bent the truth with strategic phrasing?

In situations where you haven’t been able to avoid the conversation or avoid discussion of a problem, your evasive answers may have been noticed. You may have experienced having to think on your feet under cognitive pressure in order to improvise an acceptable answer - perhaps you even had to commit to a lie rather than merely omit inconvenient truths.

These strategic layers of information management are familiar enough to all of us once it’s pointed out. Most of us can recall a time when effortful impression-management required that we adopt an honest and believable demeanour; sound plausible and present as motivated by moral principles while strategically avoiding problematic information. Parents of young children do this routinely.

Adaptive strategies to hide or disguise problematic information aim to reduce exposure or disclosure risks. Beneath our social and cognitive camouflage, some strategies work in some contexts, and for some audiences, better than others. Accordingly, avoiding, managing or manipulating information becomes more difficult the more informed the audience is - the more able they are to detect information anomalies. This is where your domain expertise matters.

In essence, we need to stop succumbing to intuitive assumptions of “deception cues” (such as micro-expressions, demeanour and body language) and start focussing on strategic information management.

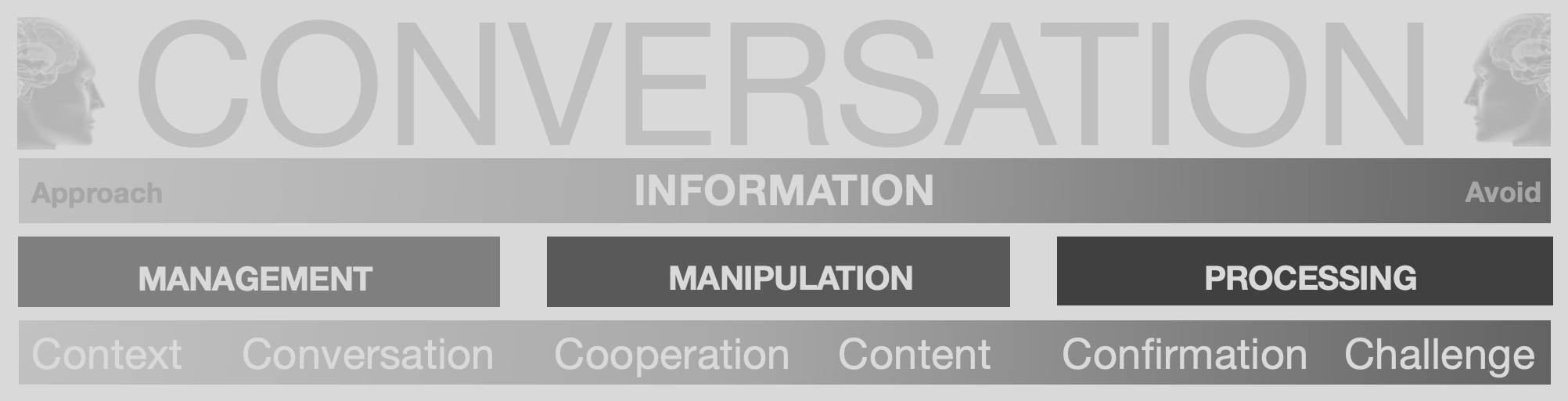

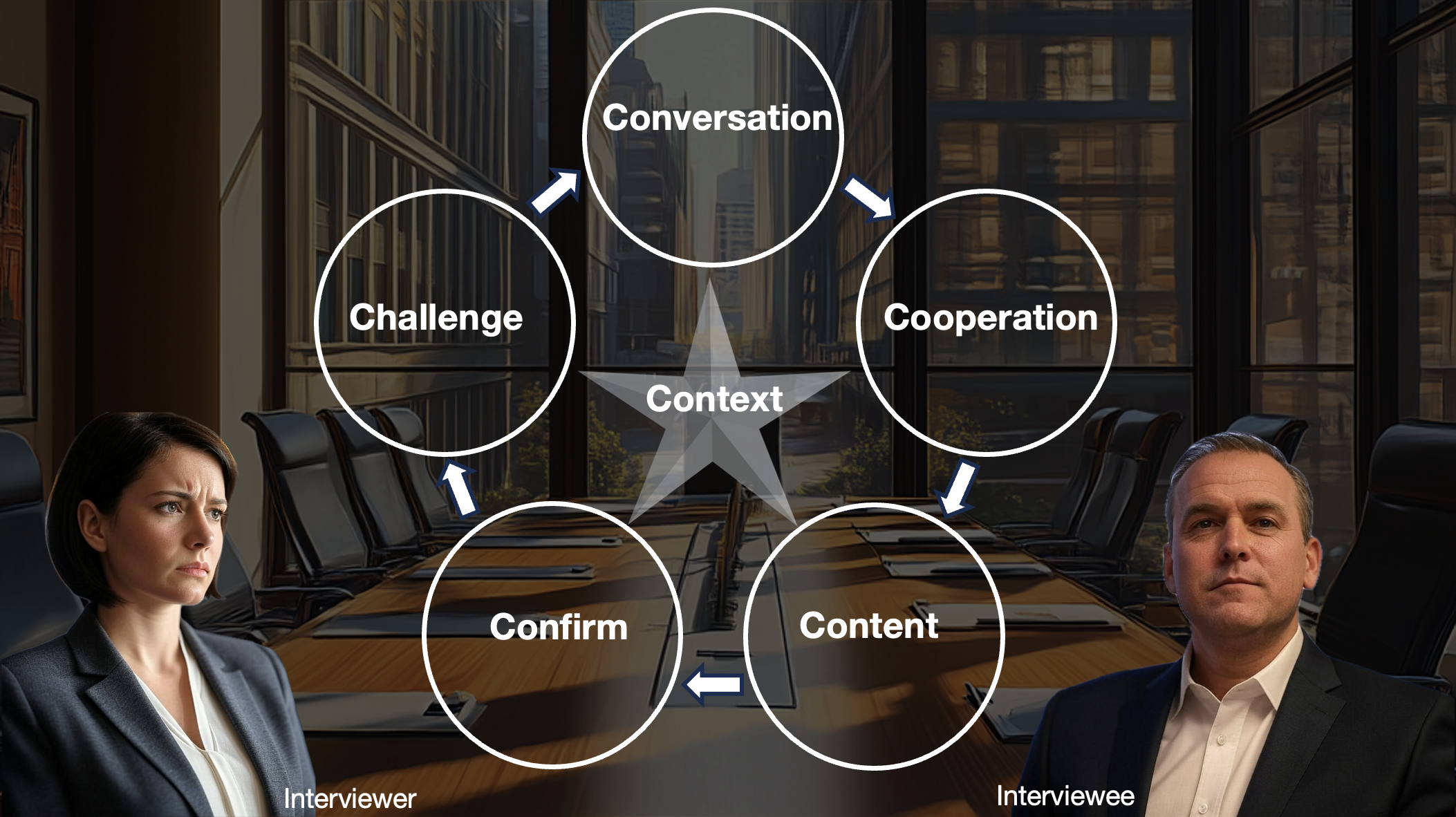

To achieve this we need to understand how information is: 1) managed in context and conversation, 2) strategically manipulated and 3) processed by deceptive interviewees in real time.

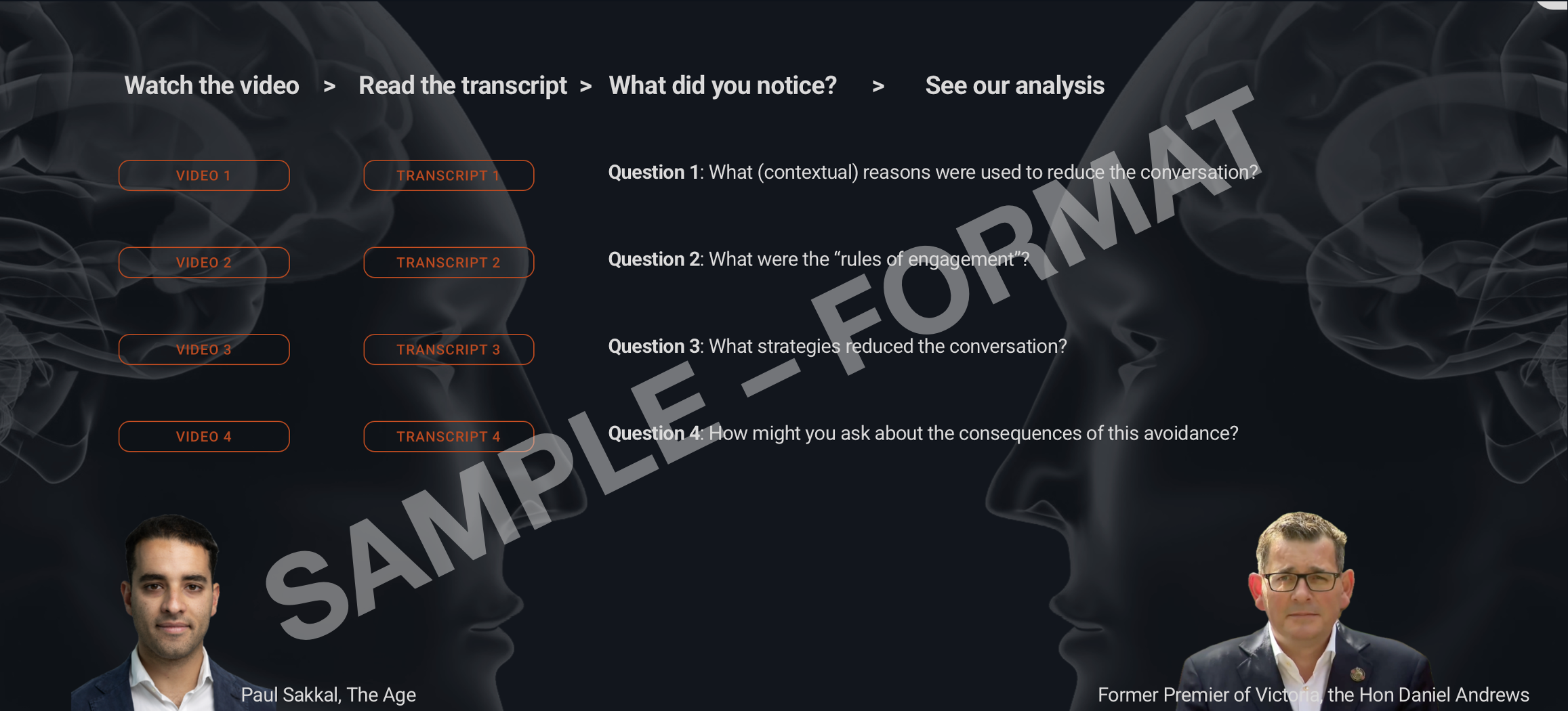

We divide these three categories into six sub-categories addressing layers of strategic information management. Each 6C layer (see below) of analysis examines what demarcates truthful from avoidant/deceptive communication, with increasing precision.

While the benefit of this layered approach is that it is flexible to your needs (you can skip contextual or conversation sections where you already have good conversational engagement) it is vital to first understand how and why some professional conversations never get off the ground to begin with - without this understanding, all subsequent efforts will be a waste of your time and energy. We can all relate to having had interactions of little to no value.

To a significant extent, our course deconstructs and reverse-engineers the task of those trying to deceive us in order to respectfully out-fox the fox.